Congratulations to New Principal, Ed Vidlak!

BVH Architecture is pleased to announce that Ed Vidlak has been promoted to a Principal of the firm. Ed’s passion for design, professionalism and leadership…

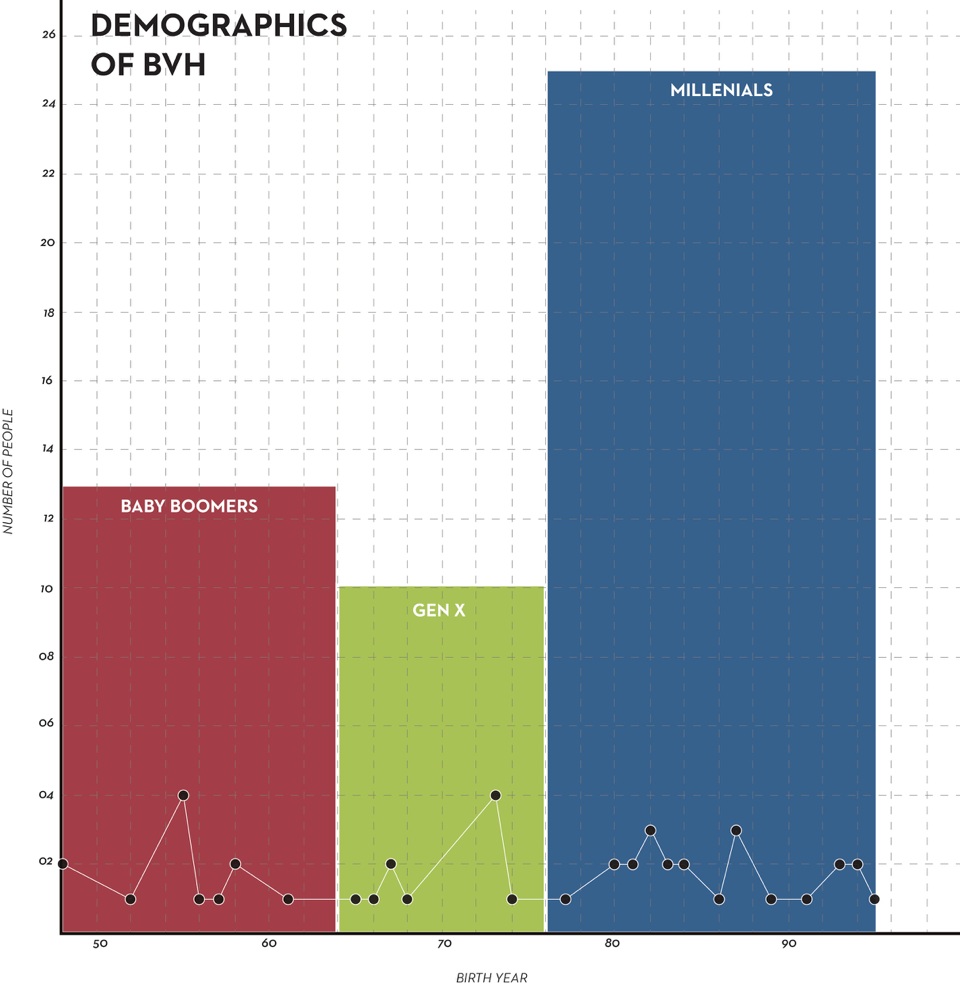

That’s not going away anytime soon. In fact, according to an article in Forbes, there will be a total of five generations in the workplace by 2020. Here at BVH, we’re well on our way. Our firm currently employs professionals from the Millennial (1977-1995), Gen X (1965-1976), and Baby Boomer (1946-1964) generation, with the fourth generation, iGen or Gen Z (1996+) creeping around the corner of employment.

But what do these “labels” teach us about meaningful interpersonal relationships with our coworkers? Forbes quotes the 2014 book, The Gen Z Effect: The Six Forces Shaping the Future of Business by Thomas Koulopoulos and Dan Keldsen in writing:

“Generational thinking is like the Tower of Babel: it only serves to divide us. Why not focus on the behaviors that can unite us?” The article goes on to suggest: “..we transpose the discussion from the focus on supporting characteristics of each generation to one that is independent on age demographics and instead on behaviors.”

Writing as a millennial, I occasionally feel the strain of outrunning negative millennial connotations. Articles with titles such as, “The Real Problem with Millennials at Work,” and “5 Shocking Statistics About Real Millennial Problems,” are certainly no help.

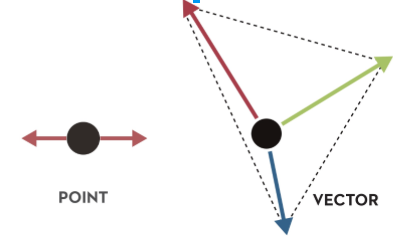

While it’s a known fact of anthropology that folks of certain time periods tend to have similar behavior patterns, I would argue each person’s generational identity should be observationally and introspectively understood as a continuous vector, rather than a stagnant point of definition.

The stereotypical attributes of each generation act as creative kryptonite when working in a collaborative environment.

The richness of our culture is because of our diverse generations. Our varying ages and consequently, areas of expertise, are to be celebrated. Ultimately, working among multiple generations is a crucial part of our culture at BVH. Our modern-day process is a far cry from Ancient Rome in that we no longer have a Master Builder who oversees the collective group that works beneath him. Rather, we operate as a creative collective in which we desire to learn from those who have more experience in areas that others do not.

Architecture in the 21st Century not only requires refined design intuition but an expertise in new materialities, sustainability, evolving modeling software – both physically and digitally – and a close analysis of the projected behavioral patterns of the newest generations who will inhabit the projects we build today. The concept of a Master Builder crumbles under the necessity to stay relevant in a quickly evolving industry.

During my time as an architecture student at UNL, I primarily worked with individuals of my generation, as Millennials made up a majority of the 2016 graduating class. Admittedly, I was caught off guard by the varying communication and design processes present within the firm when I first began. However, learning to relate and creatively interact with individuals who have vastly different life experience than myself has been an invaluable experience and, in turn, transformed my understanding and optimism towards our multi-generational workplace. Even if it means enduring endless dad jokes.